Windsor Clinic: 0800 644 0700 -

Reading Clinic: 0800 644 0900

tannereyes@sapphire-eyecare.co.uk

Windsor Clinic: 0800 644 0700 -

Reading Clinic: 0800 644 0900

tannereyes@sapphire-eyecare.co.uk

Windsor Clinic: 0800 644 0700 -

Reading Clinic: 0800 644 0900

tannereyes@sapphire-eyecare.co.uk

Windsor Clinic: 0800 644 0700 -

Reading Clinic: 0800 644 0900

tannereyes@sapphire-eyecare.co.uk

Floaters are shapes that people can see drifting across their vision. Floaters are small bits of debris floating in the vitreous jelly inside the eye. They appear in a variety of forms such as small black dots, short squiggly lines or large cobweb shapes. Short sighted people tend to suffer from them more and they increase with age. Inflammation in the eye is a rare cause of floaters.

The eye is filled with a jelly like substance called vitreous. The vitreous sits behind the pupil and lens. The jelly is made mainly of water with a meshwork holding it together. As we get older, a process known as vitreous syneresis occurs; the meshwork breaks down and pools of fluid form. The solid portion of the gel is left as debris. The debris casts shadows onto the retina, which are seen as floaters. In 70% of people, by the age of 70, the liquefied vitreous gel loses its support framework causing it to collapse. This process is known as a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD). As the vitreous gel peels away from the retina, it can cause people to see intermittent flashes of light. The flashing light will usually subside over 4 to 12 weeks, but in some patients it may take a little longer. When a posterior vitreous detachment occurs, people often become aware of a cobweb or net curtain-like floater that can be quite intrusive at first. These floater type symptoms usually improve over the first 6 months.

In the vast majority of cases floaters are harmless and represent the normal, natural (although occasionally annoying) aging change of the eye. They usually become much less obvious with time as the brain adjusts to the change and eventually filters them out. Rarely during the development of a posterior vitreous detachment, the vitreous gel can be stuck to a patch of retina and cause a tear. In some cases fluid can track through the tear, and behind the retina causing it to detach from the back of the eye a little like wallpaper peeling of a wall – a retinal detachment. This uncommon event occurs in approximately 1 in 10,000 of the population in general and usually requires urgent surgery.

Since floaters do not harm the eye and are usually well tolerated, surgery is not needed in most cases. However, some patients find their floaters particularly troublesome causing intermittent blur and problems with activities such as reading, driving or computer use. In this case it is possible to carry out an operation to the eye to remove the vitreous gel (vitrectomy), which will also remove the floaters. This course of treatment is useful in people with severe floaters who cannot adapt to them. In some patients laser treatment offers a less invasive, safer treatment to reduce symptoms. See separate information sheet.

It is impossible to remove all the vitreous gel and in some patients there are still a few floaters seen, particularly immediately after the surgery while the eye recovers. In the vast majority of people these mild symptoms are significantly better than before surgery and do not require any additional treatment.

Vitrectomy surgery is a form of keyhole surgery performed under a microscope, using 3 small incisions (1-2 mm in size) in the white of the eye. Firstly the vitreous jelly is removed (vitrectomy), and then the retina is carefully checked for any new or pre-existing holes which are usually treated with cryotherapy (freezing) to create a scar and seal the peripheral retina down securely, preventing a retinal detachment. The operation is usually completed with insertion of an intraocular air bubble. This helps close the surgical incisions and the incisions often self seal without the need for external sutures. The air bubble usually lasts in the eye for 1-2 weeks. During this time the vision will be very blurred as you cannot see through a gas bubble. If more extensive retinal breaks are found then a longer acting gas bubble may be used – up to 8 weeks

This type of vitrectomy surgery usually takes 45 minutes and can be done with the patient awake (local anaesthetic), or asleep (general anaesthetic), usually as a day case procedure. Most patients opt for a local anaesthetic, which involves a numbing injection around the eye so that no pain is felt during the operation. This is sometimes supplemented with medication to reduce anxiety (sedation).

No, this is not usual following vitrectomy for floaters. In some cases Mr Tanner may ask you to lie on one side to help push the gas within your eye against a weak area of retina after the operation.

You must not fly or travel to high altitude on land whilst the gas bubble is still in the eye

If ignored, the bubble will expand at altitude, causing very high pressure resulting in severe pain and permanent loss of vision. In addition, if you need a general anaesthetic whilst gas is in your eye, then it is vital that you tell the anaesthetist so they can avoid certain anaesthetic agents which can cause similar expansion of the bubble. None of these exclusions apply once the gas has fully absorbed. You will notice the bubble shrinking and will be aware when it has completely gone.

Most people will need two weeks off work. Your vision is reduced while the gas bubble is in the eye and this also affects depth perception.

As with any procedure, there may be risks involved and you should discuss these fully with Mr Tanner prior to your operation. In a small minority, the vision may end up worse than before the surgery, and there is a very small chance of total loss of sight. Five specific complications of vitrectomy surgery, which you should be aware of, are outlined below:

Two types of drops are usually prescribed after surgery: an antibiotic/steroid combination (eg: Tobradex) and sometimes a pressure lowering drop (eg: Iopidine). Patients are usually seen in the clinic 1-2 weeks after the surgery. If all is well, then the drops are reduced over the following 2-4 weeks. If the eye pressure is raised following surgery, additional drops and/or tablets may be prescribed to treat this.

Most people will need to change their spectacle prescription at some point after surgery.

The inside of the eye contains a jelly-like substance called the vitreous. Throughout life this fills the inside of the eye, pressing against the retina. With age this vitreous jelly changes and begins to turn into liquid. When this happens it can move away from the retina, and you will notice it as particles or floaters in the vision, occasionally associated with some flashing lights. This process is very common and in the majority of cases, although irritating, is not serious. However, if you notice floaters or flashes of light for the first time it is very important that you contact an ophthalmologist urgently to exclude the development of an associated retinal tear.

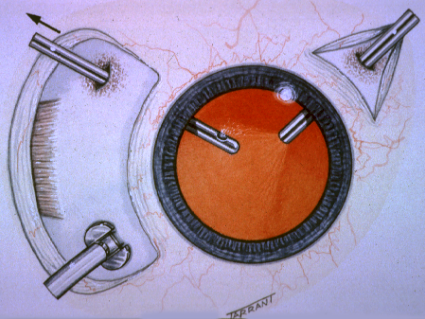

Ultrasound image showing detached vitreous gel

Unfortunately the jelly can occasionally pull on the retina and cause a retinal tear. This is a potentially serious condition, as it may progress to a retinal detachment, which can result in damage to your vision. It is extremely important that if you have sudden onset of flashes or floaters that you present promptly to an eye surgeon as a minor procedure in the outpatient department using either laser therapy or cryotherapy can treat the retinal tear and avoid major surgery and the risk of visual loss.

In the majority of people the floaters fade over a few months and become less troublesome. However, in some patients the floaters persist, obscuring central vision and causing intermittent difficulty with reading. In these patients it is possible to remove the floaters via vitrectomy surgery. This usually results in complete resolution of symptoms. As vitreoretinal surgical techniques have improved over recent years the risk associated with the surgery and the post-operative pain and discomfort has decreased dramatically. It is, therefore, now reasonable to consider vitrectomy surgery to remove floaters and vitreous debris if you are suffering persistent disturbance of your vision which interferes with normal activities such as reading.

Please contact an Ophthalmologist promptly if:

This is important as a retinal detachment may have occurred.

Disclaimer : The information provided in this website is intended as a useful aid to general practitioners, optometrists and patients. It is impossible to diagnose and treat patients adequately without a thorough eye examination by a qualified ophthalmologist, optometrist or your general practitioner. Hopefully the information will be of use prior to and following a consultation which it supplements and does not replace.